Vous souhaitez améliorer votre pratique et vos compétences en psychothérapie ? Ne cherchez plus, la formation en psychothérapie NTCV (Neuro-traitement des traumas par le champ visuel) est la solution idéale pour vous. Contrairement à la formation en psychothérapie brainspotting qui se concentre sur des techniques spécifiques, la formation NTCV vous offre une opportunité unique d’acquérir une expertise complète et approfondie dans le domaine de la psychothérapie.

La psychothérapie NTCV est une approche intégrative qui peut être parfaitement intégrée à de nombreuses autres méthodes de psychothérapie. Les thérapeutes qui maîtrisent le NTCV sont également compétents en brainspotting, ce qui leur confère une polyvalence accrue dans leur pratique. En revanche, les thérapeutes spécialisés dans le brainspotting ne sont pas automatiquement familiarisés avec le NTCV, ce qui constitue un avantage distinctif en optant pour la formation NTCV.

La formation en NTCV s’appuie sur mon parcours.

“Le docteur Zaczyk a parcouru le monde pour étudier cette technique. Il est venu dans mon cabinet de Manhattan assister à quantité de mes séances, développant ainsi une approche personnelle très originale, dont il expose dans son livre les aspects théoriques et pratiques”

Préface de David Grand

La formation en psychothérapie NTCV inclut des modules sur la théorie, les modèles et les pratiques de psychothérapie pleine conscience, ainsi que sur le traitement des traumatismes, des troubles émotionnels, dela dépression, des addictions… Cette formation vous permettra de maîtriser les concepts et les outils de psychothérapie pleine conscience, et de proposer une approche thérapeutique intégrative de haute qualité à vos patients.

Ne perdez pas de temps et inscrivez-vous dès maintenant à la formation en psychothérapie NTCV pour faire progresser votre pratique de psychothérapeute. En choisissant cette formation, vous bénéficierez d’une expertise complète et approfondie qui vous distinguera des autres professionnels de la psychothérapie. N’hésitez plus, offrez à vos patients le meilleur de la psychothérapie !

Les informations sur les dates de formation et modalités d’inscription, c’est ici.

Comme on me pose souvent la question, je vais détailler les différents points sur lesquels la formation en NTCV se distingue de la formation en brainspotting. Pour des informations complémentaires, lire l’article Formation brainspotting ou NTCV : laquelle choisir ?

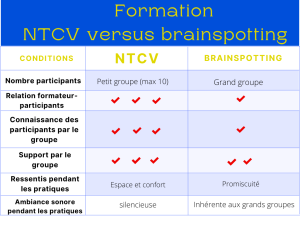

Cadre de la formation brainspotting et alternative NTCV

Les formations en psychothérapies innovantes, tout au moins avant d’être connues, ont souvent un grand nombre de participants. Il y a assez peu d’avantages et beaucoup d’inconvénients à suivre une formation dans un groupe important.

Ce tableau compare les aspects clés du cadre de la formation en psychothérapie brainspotting et en psychothérapie NTCV, mettant en évidence les différences et les similitudes en termes de nombre de participants, d’ambiance sonore, de confort, de relation formateur-groupe.

Légende :

- ✓ : Présence ou existence de l’aspect dans la formation.

- ✓✓ : Présence plus marquée ou plus grande importance de l’aspect dans la formation.

- ✓✓✓ : Présence ou importance maximale de l’aspect dans la formation.

- ✗ : Absence de l’aspect dans la formation.

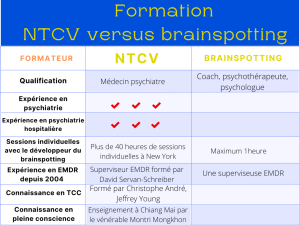

Formateurs de la formation brainspotting et NTCV

Ce tableau présente les profils des formateurs dans les formations en psychothérapie brainspotting et en psychothérapie NTCV, mettant en évidence leur expérience, leurs qualifications et leurs domaines d’expertise respectifs.

Légende :

- ✓ : Présence ou existence de l’aspect dans la formation.

- ✓✓ : Présence plus marquée ou plus grande importance de l’aspect dans la formation.

- ✓✓✓ : Présence ou importance maximale de l’aspect dans la formation.

- ✗ : Absence de l’aspect dans la formation.

- : Donnée non précisée pour cette colonne.

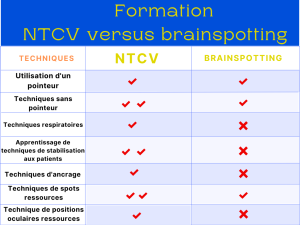

Les techniques enseignées dans la formation brainspotting et NTCV

Ce tableau récapitule les techniques spécifiques enseignées dans les formations en psychothérapie brainspotting et en psychothérapie NTCV, mettant en évidence des différences de part l’intégration dans le NTCV d’autres techniques.

Légende :

- ✓ : Présence ou existence de l’aspect dans la formation.

- ✓✓ : Présence plus marquée ou plus grande importance de l’aspect dans la formation.

- ✓✓✓ : Présence ou importance maximale de l’aspect dans la formation.

- ✗ : Absence de l’aspect dans la formation.

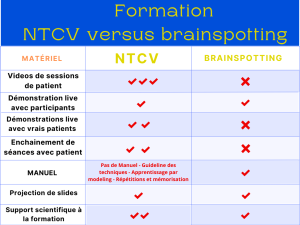

Matériel et support de la formation brainspotting et NTCV

Ce tableau compare les ressources matérielles et les supports fournis lors des formations en psychothérapie brainspotting et en psychothérapie NTCV, mettant en évidence les outils, les manuels ou les documents complémentaires mis à disposition des participants.

La formation NTCV s’appuye sur le modeling (apprentissage en regardant faire et en essayant de reproduire) et non sur le fait de partir avec un manuel qui, la plupart du temps, rejoint les autres manuels dans une armoire. L’abondance de vidéos de patients et de déroulement d’une psychothérapie NTCV, les démonstrations en direct sont une ressource précieuse qui fournissent une expérience puissante.

Légende :

- ✓ : Présence ou existence de l’aspect dans la formation.

- ✓✓ : Présence plus marquée ou plus grande importance de l’aspect dans la formation.

- ✓✓✓ : Présence ou importance maximale de l’aspect dans la formation.

- ✗ : Absence de l’aspect dans la formation.

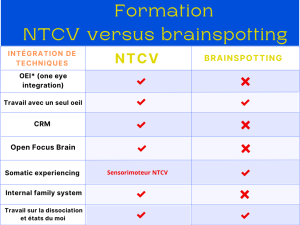

Intégration de techniques dans la formation brainspotting vs NTCV

Ce tableau renseigne sur les techniques spécifiques enseignées en psychothérapie NTCV qui la distinguent de la pratique et de la formation en psychothérapie brainspotting.

Légende :

- ✓ : Présence ou existence de l’aspect dans la formation.

- ✓✓ : Présence plus marquée ou plus grande importance de l’aspect dans la formation.

- ✓✓✓ : Présence ou importance maximale de l’aspect dans la formation.

- ✗ : Absence de l’aspect dans la formation.

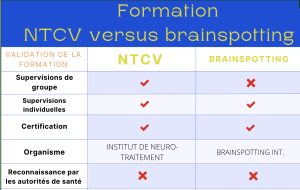

Certification formation brainspotting versus formation NTCV

Ce tableau détaille les différences de modalités de certification dans les formations en psychothérapie brainspotting et en psychothérapie NTCV.

Légende :

- ✓ : Présence ou existence de l’aspect dans la formation.

- ✓✓ : Présence plus marquée ou plus grande importance de l’aspect dans la formation.

- ✓✓✓ : Présence ou importance maximale de l’aspect dans la formation.

- ✗ : Absence de l’aspect dans la formation.

-

- : Donnée non précisée pour cette colonne.

Bibliographie formation brainspotting

David Grand « La Thérapie Brainspotting, traiter le Trauma et les somatisations » traduction 2015 Trédaniel

Corrigan F. Grand D (2013) Brainspotting : Recruiting the midbrain for accessing and healing sensorimotor memories of traumatic activation, Medical Hypotheses, 80 (2013) 759-766

Hildebrand A., Grand D., Stemmler M., (2017) Brainspotting – the efficacy of a new therapy approach for the treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in comparison to Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing, Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology VOL 5 N.1.

David. And Goldberg, Alan. This is Your Brain on Sports Grand, David. Emotional Healing at Warp Speed: The Power of EMDR Scaer, Robert. the Trauma Spectrum oidge, Norman. The Brain That Changes Itself

Seigel, Daniel. The Mindful Therapist

Bibliographie formation NTCV

Comprendre l’état de stress post-traumatique

Etat de stress aigu

Atwoli L., Stein D. J., Koenen K. C., McLaughlin K. A., « Epidemiology of post‐traumatic stress disorder : prevalence, correlates and consequences », Curr. Opin. Psychiatry, 2015, 28 (4), p. 307-311.

Berger W., Coutinho E. S., Figueira I. et al., « Rescuers at risk : A systematic review and meta‐regression analysis of the worldwide current prevalence and correlates of PtSD in rescue workers », Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol., 2012, 47, p. 1001-1011.

Brewin R., « Re‐experiencing traumatic events in PtSD : New avenues in research on intrusive memories and flashbacks », European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 2015, 6 (10), p. 3402.

Feinstein A., Owen J., Blair N., « A hazardous profession : War, journalists, and psychopathology », Am. J. Psychiatry, 2002, 159, p. 1570‐1575.

Scott K. M., Koenen K. C., Aguilar‐Gaxiola S. et al., « Associations between lifetime traumatic events and subsequent chronic physical conditions : A cross‐ national, cross‐sectional study », PLoS ONE, 2013 (11).

Van der Kolk B. A., Van der Hart O., « Pierre Janet and the breakdown of adaptation in psychological trauma », American Journal of Psychiatry, 1989, 146, p. 1530‐1540.

État de stress post-traumatique

Brewin, C., Andrews, B., Valentine, J. D. (2000). Meta-analysis of risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 748-766.

Bernat, J. A., Ronfeldt, H. M., Calhoun, K. S., Arias, I. (1998). Prevalence of traumatic events and peritraumatic predictors of posttraumatic stress symptoms in a nonclinical sample of college students. Journal of Trauma Stress, 11(4), 645-664.

Holbrook, T. L., Hoyt, D. B., Stein, M. B., Sieber, W. J. (2002). Gender differences in long-term posttraumatic stress disorder outcomes after major trauma: Women are at higher risk of adverse outcomes than men. Journal of Trauma, 53(5), 882-888.

Kilpatrick, D. G., Resnick, H. S., Milanak, M. E., Miller, M. W., Keyes, K. M., Friedman, M. J. (2013). National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. Journal of Trauma Stress, 26(5), 537-547.

Ozer, E. J., Best, S. R., Lipsey, T. L., Weiss, D. S. (2003). Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 129(1), 52-73.

Scott, M. J., Sttadling, S. G. (1994). Post-traumatic stress disorder without the trauma. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 33, 11-74.

Street, A. E., Gradus, J. L., Giasson, H. L., Vogt, D., Resick, P. (2013). Gender differences among Veterans deployed in support of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 28(Suppl 2), S556-S562.

Tolin, D. F., Foa, E. B. (2006). Sex differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: A quantitative review of 25 years of research. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 959-992.

Vogt, D., Smith, B., Elwy, R., Martin, J., Schultz, M., Drainoni, M. L., Eisen, S. (2011). Predeployment, deployment, and postdeployment risk factors for posttraumatic stress symptomatology in female and male OEF/OIF Veterans. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120, 819-831.

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. (2005). The management of PTSD in adults and children in primary and secondary care. National Clinical Practice Guideline, 26. Gaskell and the British Psychological Society.

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (n.d.). How common is PTSD in women? PTSD, National Center for PTSD. Lien

Figement dans le stress aigu

Fragkaki, I., Stathi, A., Coughtrey, A., Kaur, R., Seddon, J. L., Bifulco, A., & Pariante, C. M. (2017). Reduced freezing in posttraumatic stress disorder patients while watching affective pictures. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8, Article 39.

Gallup, G. G. Jr. (1974). Animal hypnosis: Factual status of a fictional concept. Psychological Bulletin, 81, 836-853.

Hagenaars, M., Oitzl, M., & Roelofs, G. A. (2014). Updating freeze: Aligning animal and human research. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 47, 165-176.

Humphreys, T. P., Landau, J., & Johnson, M. (2010). Tonic immobility in childhood sexual abuse survivors and its relationship to posttraumatic stress symptomatology. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25(2), 358-373.

Misslin, R. (2003). The defense system of fear: Behavior and neurocircuitry. Neurophysiology and Clinical Neurophysiology, 33(2), 55-66.

Möller, A., Söndergaard, H. P., Helström, L., & Bäckström, T. (2017). Tonic immobility during sexual assault – A common reaction predicting post-traumatic stress disorder and severe depression. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 96(8), 932-938.

Ratner, S. C., & Thompson, R. W. (1960). Immobility reactions (fear) or domestic fowl as a function of age and prior experience. Animal Behaviour, 8, 186-191.

Corrigan, F. M., Fisher, J. J., & Nutt, D. J. (2011). Autonomic dysregulation and the Window of Tolerance model of the effects of complex emotional trauma. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 25(1), 17-25.

Porges, S. W. (2003). Social engagement and attachment: A phylogenetic perspective. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1008, 31-47.

Dissociation traumatique

Ball S., Robinson A., Shekhar A., Walsh K., « Dissociative symptoms in panic disorder. », J. Nerv. Ment. Dis., 1997, 185, p. 755‐760.

Dell P. F., « Understanding dissociation », in P. F. Dell, J. A. O’Neil (dir.), Dissociation and the Dissociative Disorders : DSM-V and Beyond, Routledge, 2015.

Lanius R. A., « trauma‐related dissociation and altered states of conscious‐ ness : A call for clinical, treatment, and neuroscience research », Eur. J. Psychotraumatol., 2015, 6, 27905.

Lyssenko L., Schmahl C., Bockhacker L., Vonderlin R., Bohus M., Kleindienst N., « Dissociation in psychiatric disorders : A meta‐analysis of studies using the dissociative experiences scale », Am. J. Psychiatry, 2018, 175 (1), p. 37‐46.

Effets du stress post-traumatique sur le cerveau

Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Bremner, J. D., Walker, J. D., Whitfield, C., Perry, B. D., Dube, S. R., & Giles, W. H. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood: A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 256(3), 174-186.

Apfel, B., Ross, J., Hlavin, J., Meyerhoff, D. J., et al. (2011). Hippocampal volume differences in Gulf War veterans with current versus lifetime posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Biological Psychiatry, 69(6), 541-548.

Arnsten, A. F. T., Raskind, M. A., Taylor, F. B., & Connor, D. F. (2015). The effects of stress exposure on prefrontal cortex: Translating basic research into successful treatments for post-traumatic stress disorder. Neurobiology of Stress, 1, 89-99.

Auxéméry, Y. (2012). L’état de stress post-traumatique comme conséquence de l’interaction entre une susceptibilité génétique individuelle, un événement traumatogène et un contexte social. L’Encéphale, 38, 373-380.

Bar-Shai, M., & Klein, E. (2015). Vulnerability to PTSD: Psychosocial and demographic risk and resilience factors. In M. Safir, H. Wallach, A. Rizzo (Eds.), Future Directions in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Springer.

Bonne, O., Brandes, D., Gilboa, A., Gomori, J. M., Shenton, M. E., Pitman, R. K., & Shalev, A. Y. (2001). Longitudinal MRI study of hippocampal volume in trauma survivors with PTSD. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158, 1248-1251.

Bremner, J. D. (2006). Traumatic stress: Effects on the brain. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 8(4), 445-461.

Bremner, J. D., Elzinga, B., Schmahl, C., & Vermetten, E. (2007). Structural and functional plasticity of the human brain in posttraumatic stress disorder. Progress in Brain Research, 167, 171-186.

Drury, S. S., Theall, K., Gleason, M. M., Smyke, A. T., De Vivo, I., Wong, J. Y., Fox, N. A., Zeanah, C. H., & Nelson, C. A. (2011). Telomere length and early severe social deprivation: Linking early adversity and cellular aging. Molecular Psychiatry, 17(7), 719-727.

Etkin, A., & Wager, T. D. (2007). Functional neuroimaging of anxiety: A meta-analysis of emotional processing in PTSD, social anxiety disorder, and specific phobia. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(10), 1476-1488.

Gerritsen, L., Tendolkar, I., Franke, B., Vasquez, A. A., Kooijman, S., Buitelaar, J., Fernández, G., & Rijpkema, M. (2012). BDNF Val66Met genotype modulates the effect of childhood adversity on subgenual anterior cingulate cortex volume in healthy subjects. Molecular Psychiatry, 17(6), 597-603.

Koenigs, M., & Grafman, J. (2009). Posttraumatic stress disorder: The role of medial prefrontal cortex and amygdala. The Neuroscientist, 15(5), 540-548.

Kremen, W. S. (2012). Twin studies of posttraumatic stress disorder: Differentiating vulnerability factors from sequelae. Neuropharmacology, 62(2), 647-653.

Lyons-Ruth, K., & Block, D. (1996). The disturbed caregiving system: Relations among childhood trauma, maternal caregiving, and infant affect and attachment. Infant Mental Health Journal, 17, 257-275.

Lyons-Ruth, K. (2002). The two-person construction of defenses: Disorganized attachment strategies, unintegrated mental states, and hostile/helpless relational processes. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 2(4), 107-119.

Ng, Q. X., Yong, B. Z. J., Ho, C. Y. X., Lim, D. Y., & Yeo, W. S. (2018). Early life sexual abuse is associated with increased suicide attempts: An updated meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 99, 129-141.

O’Donovan, A., Epel, E., Lin, J., Wolkowitz, O., Cohen, B., Maguen, S., Metzler, T., Lenoci, M., Blackburn, E., & Neylan, T. C. (2011). Childhood trauma associated with short leukocyte telomere length in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 70(5), 465-471.

Shin, L. M., Rauch, S. L., & Pitman, R. K. (2006). Amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, and hippocampal function in PTSD. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1071, 67-79.

Van Harmelen, A. L., Van Tol, M. J., Van der Wee, N. J., Veltman, D. J., et al. (2010). Reduced medial prefrontal cortex volume in adults reporting childhood emotional maltreatment. Biological Psychiatry, 68(9), 832-838.

Vulliez-Coady, L., Solheim, E., Nahum, J. P., & Lyons-Ruth, K. (2016). Role-confusion in parent-child relationships: Assessing mother’s representations and its implications for counseling and psychotherapy practice. The European Journal of Counseling Psychology, 4(2), 205-227.

Wright, B., Hackney, L., Hughes, E., Barry, M., Glaser, D., Prior, V., Allgar, V., Marshall, D., Barrow, J., Kirby, N., Garside, M., Kaushal, P., Perry, A., & McMillan, D. (2017). Decreasing rates of disorganized attachment in infants and young children, who are at risk of developing, or who already have disorganized attachment. A systematic review and meta-analysis of early parenting interventions. PLoS ONE, 12(7), e0180858.

Les traumatismes psychiques complexes

Armanios, M., Blackburn, E. H. (2012). The telomere syndromes. Nature Reviews Genetics, 13, 693-704.

Drury, S. S., Theall, K., Gleason, M. M., Smyke, A. T., De Vivo, I., Wong, J. Y., Fox, N. A., Zeanah, C. H., Nelson, C. A. (2012). Telomere length and early severe social deprivation: Linking early adversity and cellular aging. Molecular Psychiatry, 17(7), 719-727.

Gerritsen, L., Tendolkar, I., Franke, B., Vasquez, A. A., Kooijman, S., Buitelaar, J., Fernández, G., Rijpkema, M. (2012). BDNF Val66Met genotype modulates the effect of childhood adversity on subgenual anterior cingulate cortex volume in healthy subjects. Molecular Psychiatry, 17(6), 597-603.

Han, L. K. M., Aghajani, M., Clark, S. L., Chan, R. F., Hattab, M. W., Shabalin, A. A., Zhao, M., Kum, G. (2018). Epigenetic aging in major depressive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(8), 774-782.

Herringa, R. J., Birn, R. M., Ruttle, P. L., Burghy, C. A., Stodola, D. E., Davidson, R. J., Essex, M. J. (2013). Childhood maltreatment is associated with altered fear circuitry and increased internalizing symptoms by late adolescence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(47), 19119-19124.

Kaszubowska, L. (2008). Telomere shortening and ageing of the immune system. Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology, 59(Suppl. 9), 169-186.

Lanius, R. A., Bluhm, R. L., Coupland, N. J., Hegadoren, K. M., Rowe, B., Théberge, J., Neufeld, R. W., Williamson, P. C., Brimson, M. (2010). Default mode network connectivity as a predictor of post-traumatic stress disorder symptom severity in acutely traumatized subjects. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 121(1), 33-40.

Opel, N., Redlich, R., Zwanzger, P., Grotegerd, D., Arolt, V., Heindel, W., Konrad, C., Kugel, H., Dannlowski, U. (2014). Hippocampal atrophy in major depression: A function of childhood maltreatment rather than diagnosis? Neuropsychopharmacology, 39(12), 2723-2731.

Ornish, D., Lin, J., Chan, J. M., Epel, E., Kemp, C., Weidner, G., Marlin, R., Frenda, S. J., Magbanua, M. J. M., Daubenmier, J., Estay, I., Hills, N. K., Chainani-Wu, N., Carroll, P. R., Blackburn, E. H. (2013). Effect of comprehensive lifestyle changes on telomerase activity and telomere length in men with biopsy-proven low-risk prostate cancer: 5-year follow-up of a descriptive pilot study. The Lancet Oncology, 14(11), 1112-1120.

Salzwedel, A. P., Stephens, R. L., Goldman, B. D., Lin, W., Gilmore, J. H., Wei, G. (2019). Development of amygdala functional connectivity during infancy and its relationship with 4-year behavioral outcomes. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 4(1), 62-71.

Shalev, I., Moffitt, T. E., Sugden, K., Williams, B., Houts, R. M., Danese, A., Mill, J., Arseneault, L., Caspi, A. (2013). Exposure to violence during childhood is associated with telomere erosion from 5 to 10 years of age: A longitudinal study. Molecular Psychiatry, 18(5), 576-581.

Van der Kolk, B. A., Courtois, C. A. (2005). Editorial comments: Complex developmental trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(5), 385-388.

Conséquences des psychotraumatismes dans l'enfance

Kim, S., Fonagy, P., Allen, J., Strathearn, L. (2014). Mothers’ unresolved trauma blunts amygdala response to infant distress. Social Neuroscience, 9(4), 352-363.

Lyengar, U., et al. (2014). Unresolved trauma in mothers: Intergenerational effects and the role of reorganization. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, article 966.

Main, M., Hesse, E. (1990). Parents’ unresolved traumatic experiences are related to infant disorganized attachment status: Is frightened and/or frightening parental behavior the linking mechanism? In M. C. Greenberg, D. Cicchetti, E. M. Cummings (Eds.), Attachment in the Preschool Years (pp. 161-182). University of Chicago Press.

Siegel, D. J. (1999). The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are. The Guilford Press.

Youssef, N. A., et al. (2018). The effects of trauma, with or without PTSD, on the transgenerational DNA methylation alterations in human offspring. Brain Sciences, 8(5), 83.

Les défaillances de la psychiatrie

Carey, B., Gebelof, R. (2018). Many people taking antidepressants discover they cannot quit. New York Times.

Orciari, H. A. (2018). Millions of Americans keep taking antidepressants for years, often because of severe withdrawal symptoms. Medical News, Physician’s First Watch.

Amos, T., Stein, D. J., Ipser, J. C. (2014). Pharmacological interventions for preventing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 7.

Gelpin, E., Bonne, O., Peri, T., Brandes, D., Shalev, A. Y. (1996). Treatment of recent trauma survivors with benzodiazepines: A prospective study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 57(9), 390-394.

Hoge, E. A., Worthington, J. J., Nagurney, J. T., Chang, Y., Kay, E. B., Feterowski, C. M., Katzman, A. R., Goetz, J. M., Rosasco, M. L., Lasko, N. B., Zusman, R. M., Pollack, M. H., Orr, S. P., Pitman, R. K. (2012). Effect of acute posttrauma propranolol on PTSD outcome and physiological responses during script-driven imagery. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics, 18(1), 21-27.

Shalev, A. Y., Ankri, Y., Israeli-Shalev, Y., Peleg, T., Adessky, R., Freedman, S. (2012). Prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder by early treatment: Results from the Jerusalem Trauma Outreach and Prevention Study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69(2), 166-176.

Wood, N. E., Rosasco, M. L., Suris, A. M., Spring, J. D., Marin, M. F., Lasko, N. B., Goetz, J. M., Fischer, A. M., Orr, S. P., Pitman, R. K. (2015). Pharmacological blockade of memory reconsolidation in posttraumatic stress disorder: Three negative psychophysiological studies. Psychiatry Research, 225(1-2), 31-39.

Stratégies d’intervention pour le traitement de l’état de stress post-traumatique

Arntz A., « Imagery rescripting as a therapeutic technique : Review of cli‐ nical trials, basic studies, and research agenda arnoud arntz », Journal of Experimental Psychopathology, 2012, 3 (2), p. 189‐208.

Cooper M. J., todd G., turner H., « the effects of using imagery to modify core beliefs : An experimental pilot study », Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 2007, 21, p. 117‐122.

Gerge A., « Revisiting safe place : Method and regulatory aspects in psychothe‐ rapy when easing allostatic overload in traumatized patients » Int. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 2018, 66 (2), p. 147‐173.

Les raisons de l’efficacité du brainspotting et du NTCV

L'utilisation du champ visuel

Micic D., Ehrlichman H., Chen R., « Why do we move our eyes while trying to remember ? the relationship between non‐visual gaze patterns and memory », Brain Cogn., 2010, 74 (3), p. 210‐224.

Nakano t., Kato M., Morito Y., Itoi S., Kitazawa S., « Blink‐related momentary activation of the default mode network », Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. uSA, 2013, 110 (2), p. 702‐706.

Paprocki R., Lenskiy A., « What does eye‐blink rate variability dynamics tell us about cognitive performance ? », Front. Hum. Neurosci., 2017, 11, p. 620.

Redgrave P., Coizet V., Comoli E., McHaffie J. G., Leriche M., Vautrelle N. et al., « Interactions between the midbrain superior colliculus and the basal ganglia », Front. Neuroanat., 2010, 4, p. 1‐8.

Chapitre 8. Méthode naturelle La pleine conscience focalisée

Germer C. K., Siegel R. D., Fulton P. R. (dir.), Mindfulness and Psychotherapy, Guilford Press, 2005.

Goleman D., The Meditative Mind : The Varieties of Meditative Experience, tarcherPerigee, 1996.

Kabat‐Zinn J., Wherever You Go, There You Are : Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life, Hyperion, 1994.

Laneri D., Krach S., Paulus F.M., Kanske P., Schuster V., Sommer J., Müller‐ Pinzler L., « Mindfulness meditation regulates anterior insula activity during empathy for social pain », Hum. Brain Mapp., 2017, 38 (8), p. 4034‐4046.

thich Nhat Hanh, Peace is Every Step : The Path of Mindfulness in Everyday Life, Bantam, 1991.

La reconsolidation de la mémoire dans le traitement des états de stress post-traumatiques

Besnard A., Caboche J., Laroche S., « Reconsolidation of memory : A decade of debate », Prog. Neurobiol., 2012, 99 (1), p. 61‐80.

Duday Y., « the neurobiology of consolidations, or, how stable is the engram ? », Annu. Rev. Psychol., 2004, 55, p. 51‐86.

Elsey J. W. B., Van Ast V. A., Kindt M., « Human memory reconsolidation : A guiding framework and critical review of the evidence », Psychol. Bull., 2018, 144 (8), p. 797‐848.

Lee J. L. C., Nader K., Schiller D., « An update on memory reconsolidation updating », Trends Cogn. Sci., 2017, 21 (7), p. 531‐545.

McKenzie S., Eichenbaum H., « Consolidation and reconsolidation : two lives of memories ? », Neuron, 2011, 71 (2), p. 224‐233.

Rodriguez‐Ortiz C. J., Bermúdez‐Rattoni F., « Determinants to trigger memory reconsolidation : the role of retrieval and updating information », Neurobiol. Learn. Mem., 2017, 142 (Pt A), p. 4‐12.

Schiller D., Monfils M. H., Raio C. M., Johnson D. C., « Preventing the return of fear in humans using reconsolidation update mechanisms », Nature, 2010, 463, p. p. 49‐53.

La double syntonie

Adamson L., Frick, J. « the still face : A history of a shared experimental para‐ digm », Infancy, 2003, 4 (4), p. 451‐473.

Reindl V., Gerloff C., Scharke W., Konrad K., « Brain‐to‐brain synchrony in parent‐child dyads and the relationship with emotion regulation revealed by fNIRS‐based hyperscanning », NeuroImage, 2018, 178, p. 493‐502.

Tronick E., Adamson L. B., Als H., Brazelton t. B., « Infant emotions in normal and pertubated interactions », présenté à la biennale de la Society for Research in Child Development, Denver, avril 1975. (L’expérience du visage impassible du Dr Edward tronick est visible à l’adresse www.bit.ly/livreDRZ.)

Zimmer, C. (2011). 100 trillion connexions. Scientific American, 304, 58-63.

Leong, V., Byrne, E., Clackson, K., Georgieva, S., Lam, S., Wass, S. (2017). Speaker gaze increases infant-adult connectivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(50), 13290-13295.

Morito, Y. (2017). Eye contact with your baby helps synchronize your brainwaves. Science Daily, 29 novembre 2017.

Reindl, V., Gerloff, C., Scharke, W., Konrad, K. (2018). Brain-to-brain synchrony in parent-child dyads and the relationship with emotion regulation revealed by fNIRS-based hyperscanning. NeuroImage, 178, 493-502.

Saito, D. N., Tanabe, H. C., Izuma, K., Hayashi, M. J., Morito, Y., Komeda, H., Uchiyama, H., Kosaka, H., Okazawa, H., Fujibayashi, Y., Sadato, N. (2010). « Stay tuned »: Inter-individual neural synchronization during mutual gaze and joint attention. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 4, article 127, 1-12.

La Présence du psychothérapeute

Porges S. W., « the polyvagal theory : New insights into adaptive reactions of the autonomic nervous system », Cleve. Clin. J. Med., 2009, 76 (suppl. 2), p. S86‐S90.

Porges S. W., « Neuroception : A subconscious system for detecting threat and safety », Zero to Three. Bulletin of the National Center for Clinical Infant Programs, 2004, 24 (5), p. 19‐24.

Comment marche le Brainspotting ?

Corrigan F. M., Grand D., Raju R., « Brainspotting : Sustained attention, spinothalamic tracts, thalamocortical processing, and the healing of adaptive orientation truncated by traumatic experience », Medical Hypotheses, 2015, 84, p. 384‐394.

Corrigan F. H., Grand D., « Brainspotting : Recruiting the midbrain for acces‐ sing and healing sensorimotor memories of traumatic activation », Medical Hypotheses, 2013, 80, p. 759‐766.

Critchley H. D., « Neural mechanisms of autonomic, affective, and cognitive integration » J. Comp. Neurol., 2005, 493, p. 154‐166.

Hildebrand A., Grand D., Stemmler M., « Brainspotting – the efficacy of a new therapy approach for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disor‐ der in comparison to eye movement desensitization and reprocessing », Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology, 2017, 5 (1).

Masson J., Bernoussi A., Moukouta C. S., « Brainspotting therapy : About a Bataclan victim », Global Journal of Health Science, 2017, 9 (7), p. 103‐107. Micic D., Ehrlichman H., Chen R., « Why do we move our eyes while trying to remember ? the relationship between non‐visual gaze patterns and memory », Brain Cogn., 2010, 74, p. 210‐224.

Patrícia F. M., José F. P., de F, Marcelo M., « Persistent genital arousal disorder as a dissociative trauma related condition treated with brainspotting – A suc‐ cessful case report », Int. J. Sch. Cog. Psychol., 2015, S1, 002.

Rempel Clower N. L., « Role of orbitofrontal cortex connections in emotion », Ann. NY Acad. Sci., 2007, 1121, p. 72-86.

Schore A., « Attachment and the regulation of the right brain », Attachment and Human Development, 2000, 2 (1), p. 23-47.

Schmidt R. et al., Report of Findings from the Community Survey september 2016, Newtown Sandy Hook Community Foundation, www.bit.ly/ZREPORt. Van der Kolk B., « Clinical implications of the neuroscience research in PtSD », Ann. NY Acad. Sci., 2006, 1071, p. 277-293.

Zimmer C., « 100 trillion connexions », Scientific American, 2011, 304, p. 58‐63.

Puissance du NTCV

Raichle M. E., « the brain’s default mode network », Annu. Rev. Neurosci., 2015, 38, p. 413-427.

Raichle M. E., Snyder A. Z., « A default mode of brain function : A brief history of an evolving idea », NeuroImage 2007, 37 (4), p. 1083‐1090.

Provine R. R., « Yawning : no effect of 3‐5 % CO2, 100 % O2, and exercise », Behav. Neural Biol., 1987, 48 (3), p. 382‐393.

Provine R. R., « Yawning », American Scientist, 2005, 93, p. 532‐535.

Versus

Hildebrand A., Grand D., Stemmler M., « Brainspotting – the efficacy of a new therapy approach for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disor‐ der in comparison to eye movement desensitization and reprocessing », Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology, MJCP, 2017, 5 (1).

Les ouvrages de référence pour la formation NTCV

Breggin, P. (2007). Your Drug May Be Your Problem: How and Why to Stop Taking Psychiatric Medications. Da Capo Lifelong Books.

Damasio, A. (1999). Le Sentiment même de soi. Odile Jacob.

Doidge, N. (2008). Les Étonnants Pouvoirs de transformation du cerveau. Belfond.

Ferenczi, S. (2006). Le Traumatisme. Payot et Rivages, « Petite Bibliothèque Payot ».

Grand, D. (2013). Brainspotting: the Revolutionary New Therapy for Rapid and Effective Change. Sounds true.

Grand, D. (2001). Emotional Healing at Ward Speed: the Power of EMDR. Harmony Books.

Grand, D. (2014-2015). Brainspotting: Training Manual Phase 1, Phase 2, Phase 3.

Grand, D. (2018). Brainspotting: Training Manual Phase 4, Atlanta, 7-9 décembre.

LeDoux, J. (2005). Le Cerveau des émotions. Les mystérieux fondements de notre vie émotionnelle. Odile Jacob.

Levine, P. (2013). Réveillez le tigre. Interéditions.

Meichenbaum, D. (1995). A Clinical Handbook: Practical Therapist Manual for Assessing and Treating Adults with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the Body: A Sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy. Norton.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-regulation. Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology.

Ross, C. (2006). The Trauma Model. Manitou Communications.

Ross, C. (2008). The Great Psychiatry Scam: One Shrink’s Personal Journey. Manitou Communications.

Scaer, R. (2014). The Body Bears the Burden. Routledge.

Scaer, R. (2005). The Trauma Spectrum: Hidden Wounds and Human Resiliency. Norton.

Schore, A. (2016). Affect Regulation and the Origin of the Self. Routledge.

Servan-Schreiber, D. (2003). Guérir, le stress, l’anxiété, la dépression, sans médicaments ni psychanalyse. Robert Laffont.

Shapiro, F. (2007). Manuel d’EMDR (Intégration neuro-émotionnelle par les mouvements oculaires). Principes, protocoles, procédures. Interéditions.

Siegel, D. J. (1999). The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are. Guilford Press, 2e édition.

Stern, D. (2003). Le Moment présent en psychothérapie. Un monde dans un grain de sable. Odile Jacob.

Valabrega, J.-P. (1994). La Formation du psychanalyste. Esquisse d’une théorie. Payot.

Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain and Mind in the Transformation of Trauma. Penguin Books.

Van der Hart, O., Nijenhuis, E. R. S., & Steele, K. (2006). The Haunted Self: Structural Dissociation and the Treatment of Chronic Traumatization. W.W. Norton and Co.

ZACZYK, C. (2019). Guérir des traumatismes avec le Brainspotting. Odile Jacob.

#formationbrainspotting #formationNTCV